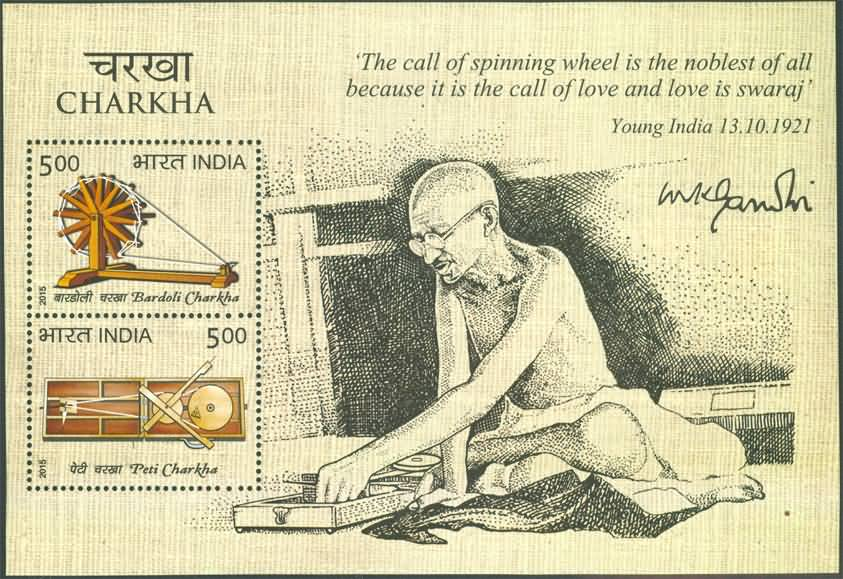

Charkha (spinning wheel)

Technical Data

| Date of Issue | October 15, 2015 |

|---|---|

| Denomination | Rs. 10 |

| Quantity | 200,000 |

| Perforation | 13½ |

| Printer | Security Printing Press, Hyderabad |

| Printing Process | Wet Offset |

| Watermark | No Watermark |

| Colors | Multicolor |

| Credit (Designed By) | Sh. Sankha Samanta Smt. Alka Sharma |

| Catalog Codes |

Michel IN BL131 Stamp Number IN 2745a Yvert et Tellier IN BF122 Stanley Gibbons IN MS3098 |

| Themes | Crafts | Professions |

Origins of the Spinning Wheel in India

The Charkha, or spinning wheel, is a simple yet ingenious device used to spin thread or yarn from natural or synthetic fibres. It replaced the ancient hand-spindle method and soon became a familiar presence in Indian households. Excavations at Harappa and Mohenjo-Daro confirm the antiquity of spinning practices in India, while early references to spinning and weaving appear in the Rig Veda, highlighting the craft’s deep cultural roots.

Historical Mentions and Early Significance

The Arthashastra of Kautilya (4th century B.C.) alludes to the spinning wheel, further establishing its ancient lineage. It describes the Charkha as a tool for drawing, twisting, and winding fibres, and mentions the important state official, the Sutradhyaksha, or Head of the Yarn Section. Through centuries, the Charkha served as an essential livelihood tool. Artisans treated it with reverence, often tying sacred threads and burning incense before beginning their work.

Role in Household Economy and Textile Craft

Traditionally, spinning was carried out by women at home, providing both income and empowerment. The entire chain—from picking cotton to carding, slivering, spinning, and weaving—was performed by hand, demanding tremendous skill and patience. Travellers such as Marco Polo marveled at the fineness of Indian cotton fabrics, comparing them to a spider’s web. During the Mughal era too, spinning and weaving flourished as vital domestic occupations.

Indian Textiles and Conflict with European Trade

From the 16th century onward, foreign traders—the Portuguese, Dutch, French, and British—exported Indian handmade textiles to Europe, where they were prized for their delicacy. This popularity, however, led to fierce opposition from English manufacturers. The British Parliament imposed heavy duties on Indian cloth and even penalised its use in England. Subsequently, Britain began importing raw cotton from India and selling cheap machine-made cloth back to Indian markets. This devastated the traditional spinning and weaving community, plunging artisans into poverty.

Mechanization and Its Impact on Rural India

The establishment of the first textile mill in Bombay in 1854 marked the beginning of large-scale mechanization in India. As mills multiplied, traditional hand-spinning declined rapidly. Rural life was deeply affected, as villagers who depended on spinning and weaving for sustenance struggled to compete with machine-made textiles.

The Charkha in India’s Freedom Struggle

During the national movement, the Charkha emerged as a powerful symbol of the Swadeshi movement. Mahatma Gandhi encouraged Indians to reject foreign cloth and embrace Indian hand-spun khadi. The spinning wheel became a means to alleviate rural poverty, promote self-sufficiency, and resist the economic exploitation inflicted by British industries.

Gandhiji’s Philosophy of the Charkha

For Mahatma Gandhi, the Charkha held profound spiritual and moral meaning. He described it as “the ever-moving wheel of the Divine law of love,” symbolizing self-reliance, dignity of labour, nonviolence, and human values. To him, spinning was an act of devotion—one that uplifted the spirit and strengthened the nation.

Gandhiji believed that reviving hand-spinning and hand-weaving would regenerate India both economically and morally. He emphasized that the Charkha supported numerous auxiliary village industries—ginning, carding, dyeing, sizing, warping, and weaving—thus sustaining an entire ecosystem of rural craftsmanship.

Gandhi’s Call for National Commitment

Ahead of the AICC meeting in 1924, Gandhi issued a powerful appeal about the dual nature of the spinning wheel. In its “terrible” aspect, it represented economic boycott of foreign goods; in its “benign” aspect, it offered hope and livelihood to the rural masses. In 1921, the Congress Working Committee launched a national programme for Khadi promotion, establishing the All India Spinners’ Association, widely known as the Charkha Sangh.

Innovation and the Portable Charkha

Determined to improve the productivity of the Charkha, Gandhiji invited designs for a more efficient, user-friendly, and affordable spinning wheel. During his imprisonment in Yeravda Jail, he personally developed a portable Charkha, compact enough to be carried anywhere—an innovation that made spinning accessible to all.

Depicting the Charkhas on Stamps

This special set of two stamps showcases:

- The traditional Charkha, symbolising India’s ancient spinning heritage.

- The portable Charkha, designed by Mahatma Gandhi, representing innovation, swadeshi, and the spirit of self-reliance.

Together, they honour the Charkha’s enduring legacy as a national emblem of simplicity, craftsmanship, and freedom.

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.