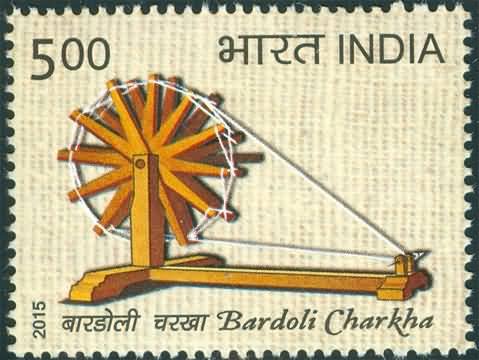

Bardoli Charkha or The Traditional Charkha

Technical Data

| Date of Issue | October 15, 2015 |

|---|---|

| Denomination | Rs. 5 |

| Quantity | 500,000 |

| Perforation | 13½ |

| Printer | Security Printing Press, Hyderabad |

| Printing Process | Wet Offset |

| Watermark | No Watermark |

| Colors | Multicolor |

| Credit (Designed By) | Sh. Sankha Samanta Smt. Alka Sharma |

| Catalog Codes |

Michel IN 2889 Stamp Number IN 2744 Yvert et Tellier IN 2637 Stanley Gibbons IN 3096 |

| Themes | Crafts | Professions |

Introduction

The Traditional Charkha, or spinning wheel, is one of India’s oldest and most iconic implements, used for spinning thread or yarn from natural fibers. Its origins date back thousands of years, with archaeological findings at Harappa and Mohenjo-Daro revealing early evidence of spinning practices. References to spinning and weaving are also found in the Rig Veda, highlighting the deep cultural and historical roots of this craft.

Antiquity and Early References

The Arthashastra of Kautilya (4th century B.C.) provides one of the earliest textual references to spinning. It mentions the Sutradhyaksha, or Head of the Yarn Section—proof that spinning was already an established and organized activity in ancient India. The Charkha evolved over centuries, reflecting the vast textile tradition that India became renowned for.

Role in Household and Livelihood

For generations, the Traditional Charkha was a familiar presence in Indian homes. Women commonly used it to spin yarn, contributing significantly to household income. Artisans treated the Charkha with reverence—tying sacred threads, lighting incense, and offering prayers before beginning their work.

The entire process of cotton transformation—picking, carding, slivering, spinning, and weaving—was performed by hand and required exceptional skill. Travelers like Marco Polo admired Indian cotton fabrics for their unmatched fineness, comparing them to a spider’s web.

Decline During Colonial Rule

During the 16th century, the arrival of European traders boosted the demand for India’s handmade textiles. However, as Indian fabrics flooded European markets, British manufacturers protested, prompting Parliament to impose heavy duties on Indian textiles.

This led to a shift: England imported raw cotton from India but exported cheap, machine-made cloth back to the subcontinent, drastically reducing the demand for hand-spun and hand-woven products.

The establishment of the first textile mill in Bombay in 1854 accelerated industrialization, causing the traditional spinning craft to decline and weakening the rural economy.

The Charkha as a Symbol of Swadeshi

The Traditional Charkha gained renewed significance during India’s freedom struggle. It became a powerful emblem of the Swadeshi Movement, which urged Indians to reject foreign goods and embrace indigenous, handmade products.

The Charkha symbolized economic independence, rural empowerment, and resistance to colonial exploitation. Spinning at home became both a political statement and a source of livelihood for millions.

Gandhiji’s Interpretation

Mahatma Gandhi brought profound philosophical meaning to the Traditional Charkha. To him, it embodied:

- Self-reliance

- Nonviolence

- Dignity of labour

- Simplicity and self-discipline

- Economic upliftment of villages

He believed that reviving traditional hand-spinning and weaving would morally and economically regenerate the nation. Gandhi described the Charkha as “the hope of the masses,” linking it to numerous village industries that sustained rural life.

Representation in the Commemorative Stamp

The commemorative stamp issued by the Department of Posts showcases the Traditional Charkha, honouring its historical depth, cultural legacy, and role in shaping India’s socio-economic fabric. It pays tribute to the countless artisans, spinners, and freedom fighters for whom the Charkha was both a tool of livelihood and a symbol of national pride.

Conclusion

More than a spinning device, the Traditional Charkha represents India’s civilizational continuity, its struggle for self-reliance, and the enduring dignity of handcraft.

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.